By Khadija Khan

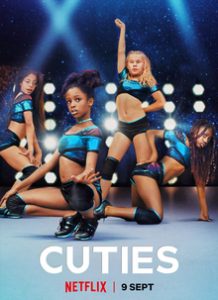

The Netflix film Cuties, directed by Franco-Senegalese Filmmaker Maïmouna Doucouré, has caused a lot of controversy. The coming-of-age movie shows very young girls in France dressed inappropriately for their age and performing highly sexualised dance routines. As a result, there have been calls for Netflix to ban the movie; Doucouré has also received death threats for having made such a film.

In Cuties (‘Mignonnes’ in French), we see 11-year-old Amy, a lonely and alienated French girl of Senegalese origin, who is caught between her own immigrant culture, which is traditional and conservative, and the hypersexualised culture of western society, which objectifies women.

The sexualisation of little girls is appalling in all forms and it can traumatise innocent children, often leaving them scarred for the rest of their lives. Cuties, in my opinion, is an effort to shed light on this important subject.

The movie largely identified the dangers and challenges immigrant children face, both in their own highly conservative culture, as well as the world outside. It shows the negative effects of western youth culture, fuelled by the rise of social media, and so-called Muslim community standards as biased and prejudiced towards women – and rightly so.

Cuties’ Amy is visibly frustrated and puzzled as she tries to cope with her circumstances. Her disconnect from her community is evident when she abhors the idea of being submissive; at a religious gathering, she is lectured to about the ‘correct’ behaviour of women in Islam. Meanwhile her mother, Mariam, is grief-stricken after being abandoned by her husband, who has married another woman. Rather than protesting at this callous behaviour, Mariam isn’t even allowed to complain. Instead, she is expected to welcome her husband and his second wife graciously as they prepare to all live together in the same home.

It is against this backdrop of religious and traditional oppression in her family that Amy decides to rebel. However, due to the lack of guidance and naivety, she is unable to navigate her anger and anguish in a safe way. Desperate to escape the confines of her suffocating home life, she meets a group of girls who are completely different – with their outrageous clothes and their ambitions to be the best dancers in a city competition.

The movie depicts the all-too familiar vicious circle of abuse that pushes vulnerable children even further into more isolation and other forms of harm and abuse.

But what is interesting to note is that while the sexualisation of young children in Western youth culture is condemned emphatically, religious misogyny and sexualisation of little girls under the guise of ‘modesty’ in Muslim culture is still largely seen as ‘conservative mores’ here in the West. And this is something that should be discussed more candidly

It is sad how girls in conservative Muslim households are robbed of their childhood and wrapped up in burqas and hijabs. They are forced to adopt a ‘modest’ lifestyle for which they are physically and mentally unprepared. They become women sooner than they should be.

Sadly, the critics of Cuties ignore this type of sexualisation of girls done in the name of religion, and instead focus on the hypersexualisation in the western entertainment industry. On such person is Katharine Birbalsingh, head of the Michaela Community School in north London, who claims that Cuties “does an excellent job of ticking off men’s fetishes with the girls.”

In fairness, her concerns are genuine; the sexualisation and objectification of children – such as encouraging young girls to take part in beauty pageants – should be scrutinised. But Birbalsingh’s silence over girls as young as four made to wear hijab in primary schools is deafening.

Ironically, this misogynistic and extremist mindset to cover little girls in religious garments thrives under the pretext of ‘cultural cohesion’. The tragedy is that this has become a reasonable enough excuse for the concerned authorities to comply with ever-growing demands of sections of certain communities.

As a headteacher in a multicultural city, I’m sure Birbalsingh must have seen little girls going through this ordeal on a regular basis. And yet, it seems, she didn’t feel a responsibility to raise her voice against this rampant sexualisation of little girls done in the name of religious ‘modesty’?

One should bear in mind that, with all its flaws and imperfections, the rights western women enjoy in free societies are a culmination of the continuous struggle, spanning over many decades, for the right of women to live with dignity. On the other hand, certain Muslim communities are far from providing even basic human rights for females within their own families, let alone being equal to men.

At the core of Cuties is the reality of how adolescent children go through different phases at their own pace. They experiment with certain trends and ideas to express themselves and their emotions. Most of the time this will be innocuous and they will grow out of it. However, in extreme cases, some of their actions will have a damaging effect on their mental and physical well-being.

Our primary concern, therefore, should be the protection of gullible and impressionable children – regardless of their religious and cultural affiliations. Demonising girls (such as the ones portrayed in Cuties) by equating their naive and thoughtless acts with “whores” and women seeking sexual attraction from men is highly incautious.

Perhaps this mindset was a part of the reason why so many grooming gang victims got abandoned by the society, police, and social workers. They weren’t seen as worthy enough to be protected.

According to victims’ accounts, they were never seen as abused children. Instead they were treated as prostitutes who had chosen a promiscuous lifestyle.

People need to understand that not all vulnerable girls return to their normal lives after being led astray. They can be abused and exploited further if not looked after – and perhaps this is the message that the film tried to bring into the spotlight.

Cuties may have glorified the rebellious and hypersexualised behaviour of the children portrayed in the movie, but these are realities that very much exist in the modern West.

Amy’s eventual return to her family is cry for unconditional love and care that every child deserves. And what Amy’s mother did by embracing her daughter is an act of that very unconditional love of a parent who, despite having her own wings clipped, wants nothing more than to see her little girl spread her wings and fly high up to unlimited skies.

Overall, Cuties should not be judged so harshly. Rather, it should be seen as a wake up call to society that, whether it is through a hypersexualised pop culture or religious modesty, vulnerable children remain at risk of being left alone to suffer in silence, if not protected.

* Main Pic credit: Netflix

Khadija Khan is a journalist and commentator based in the UK. You can follow her on Twitter.